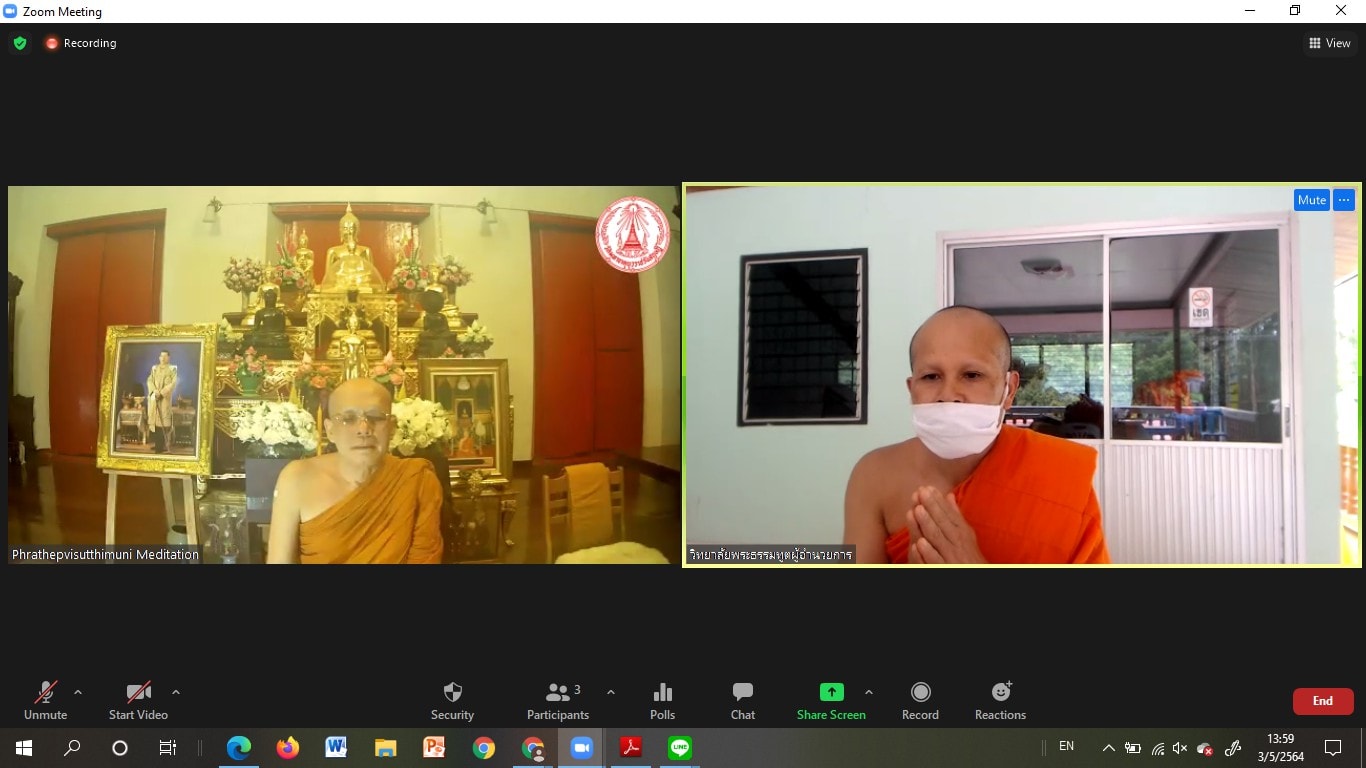

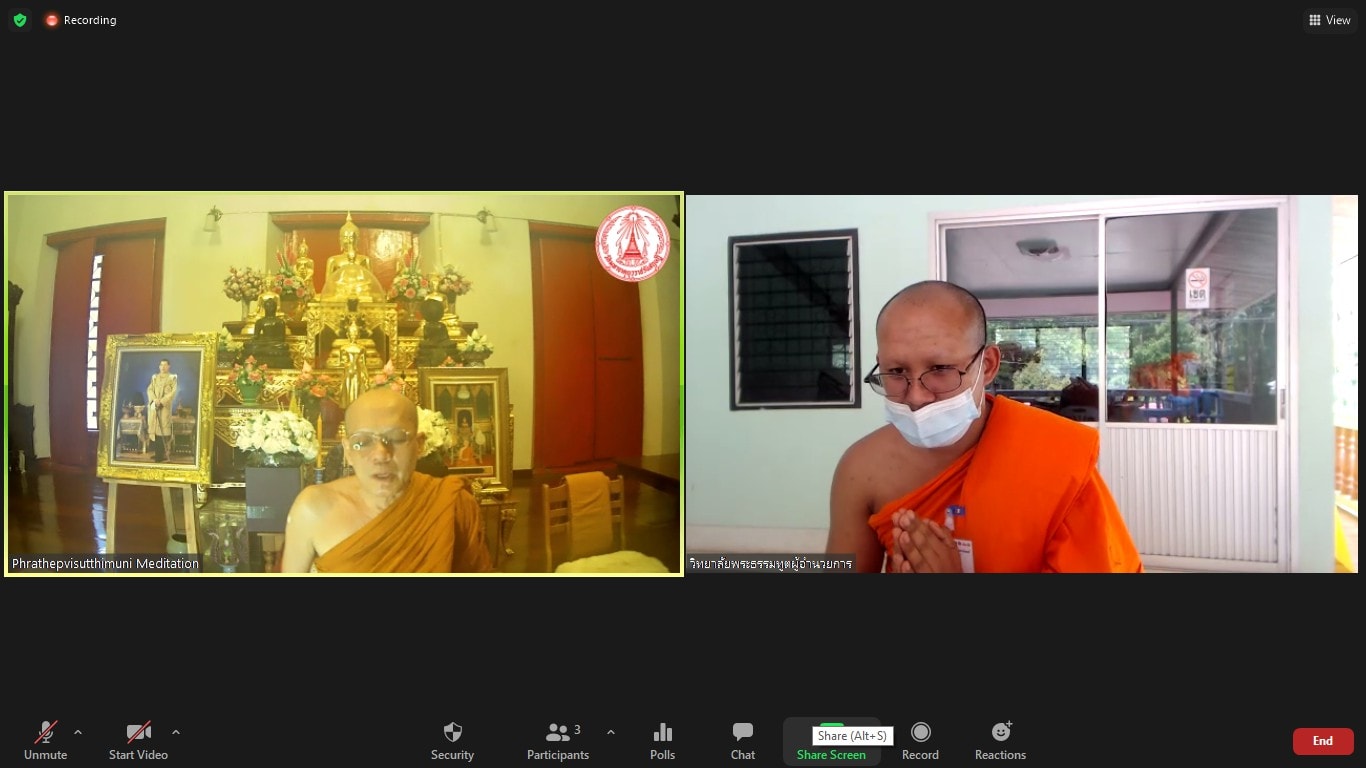

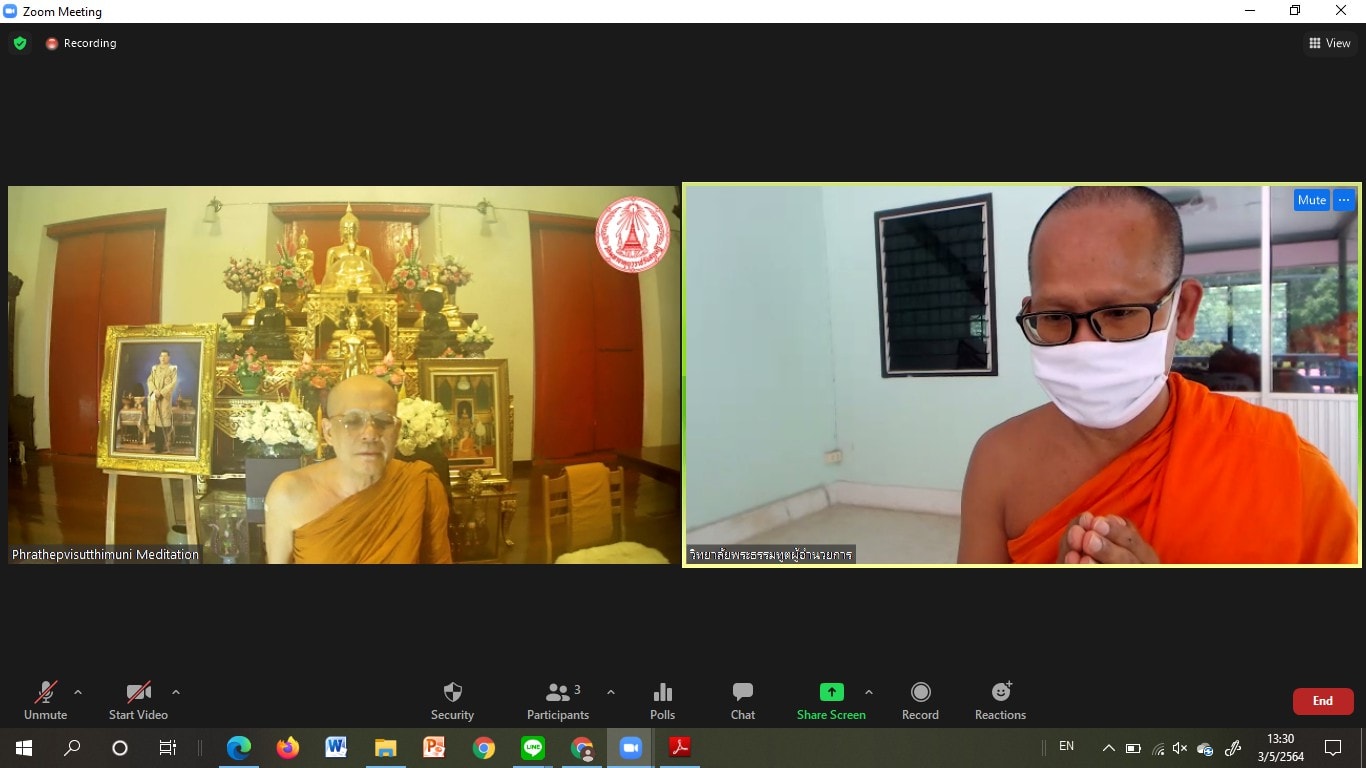

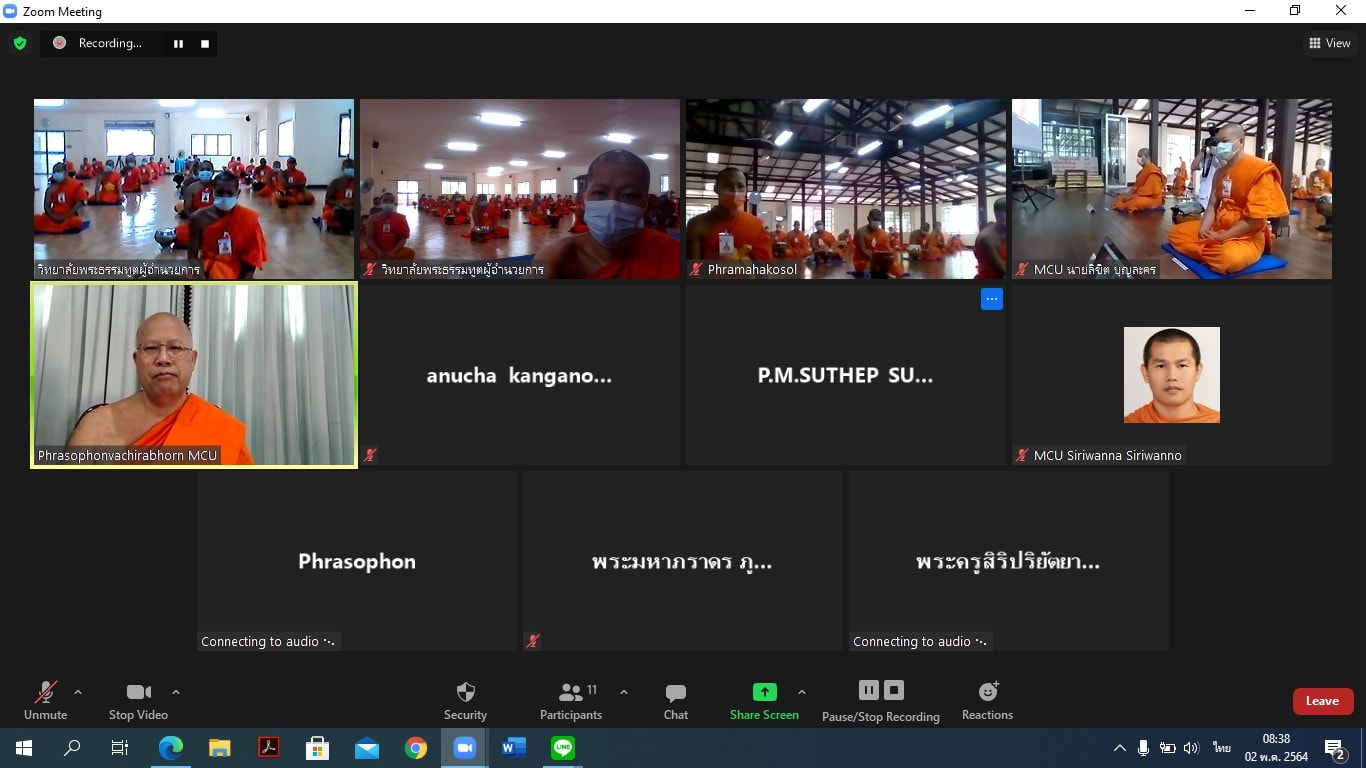

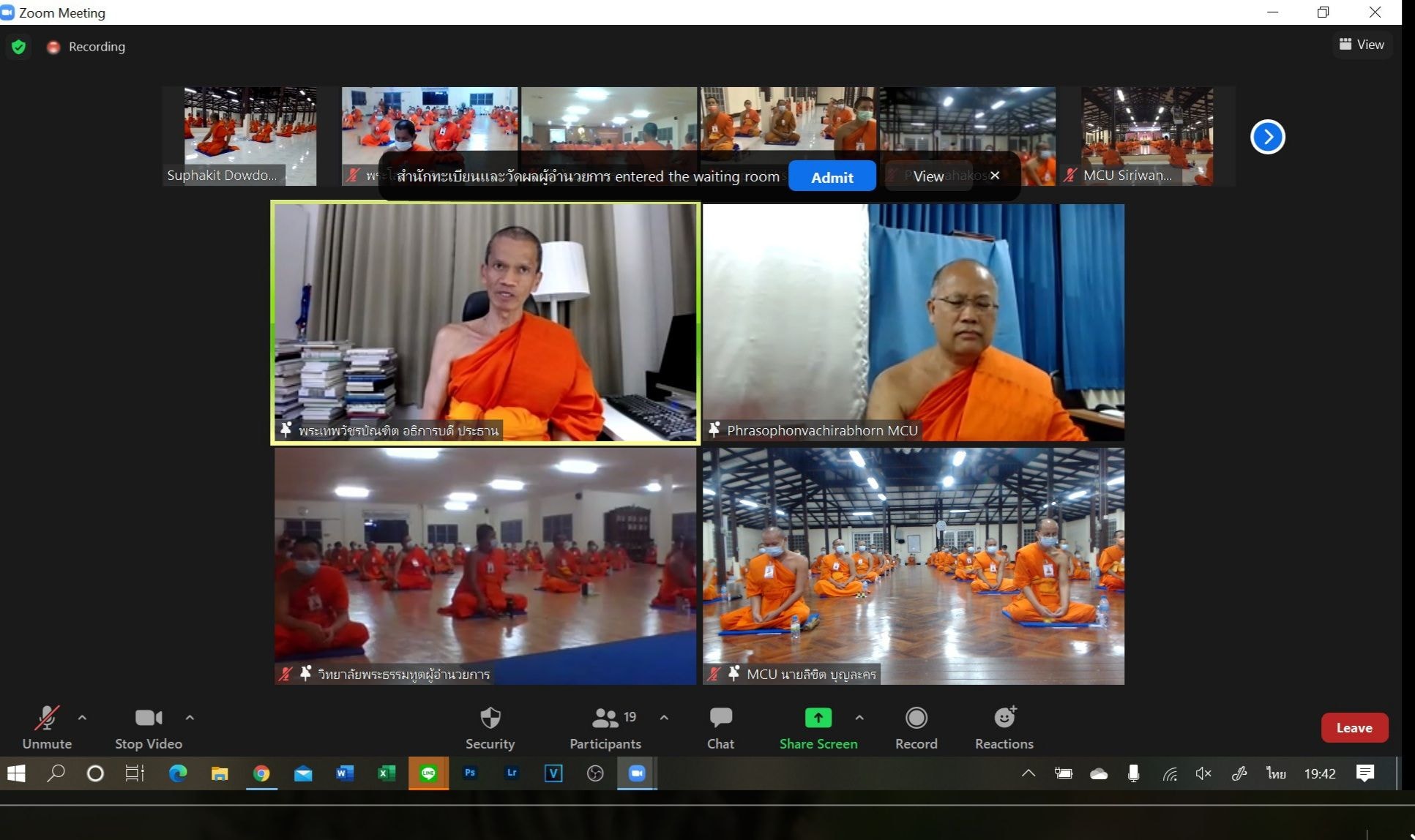

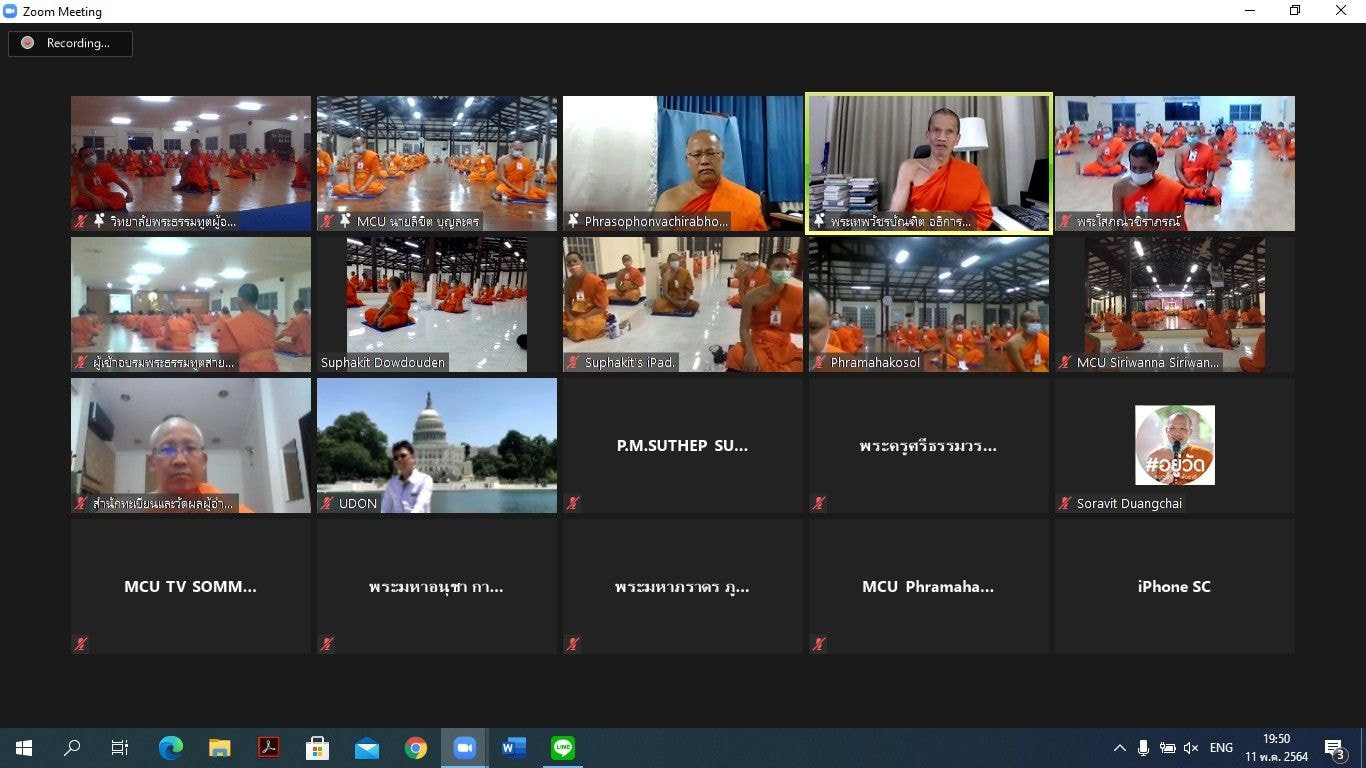

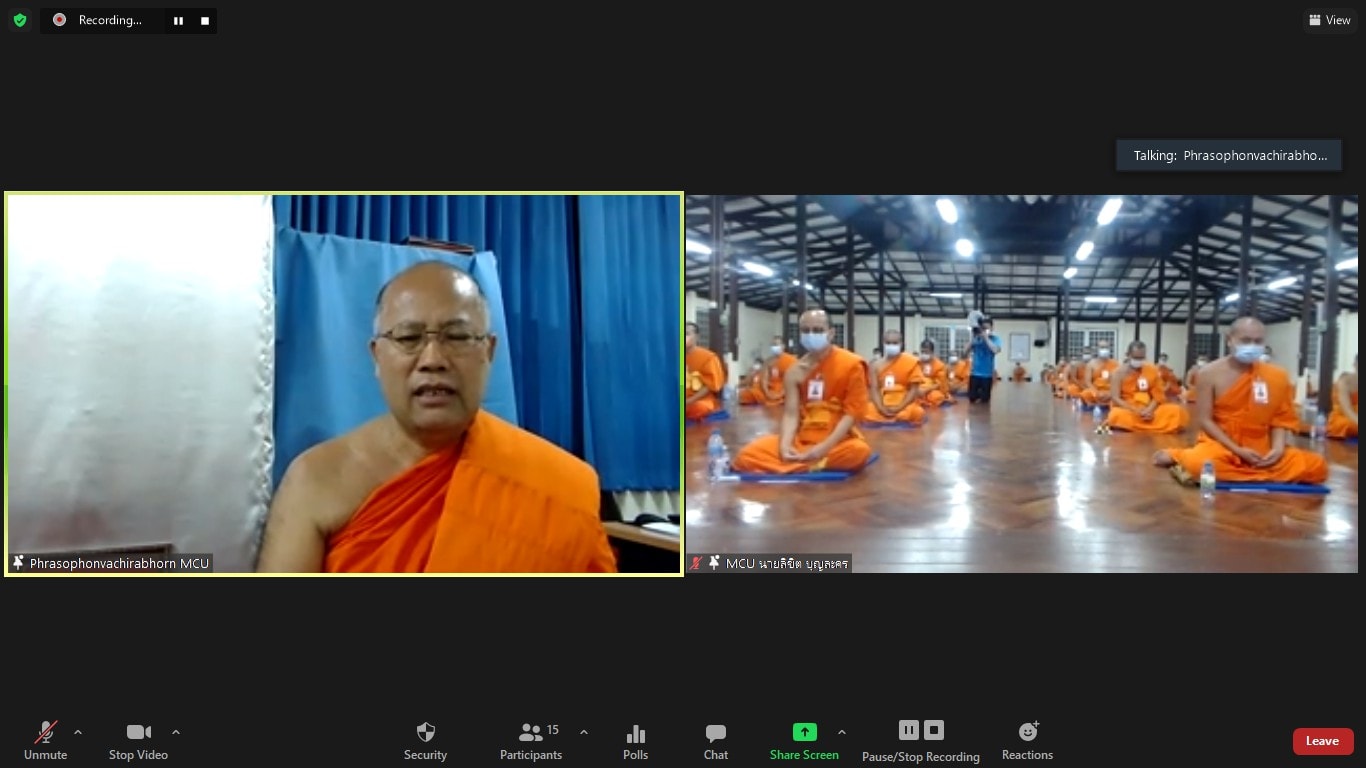

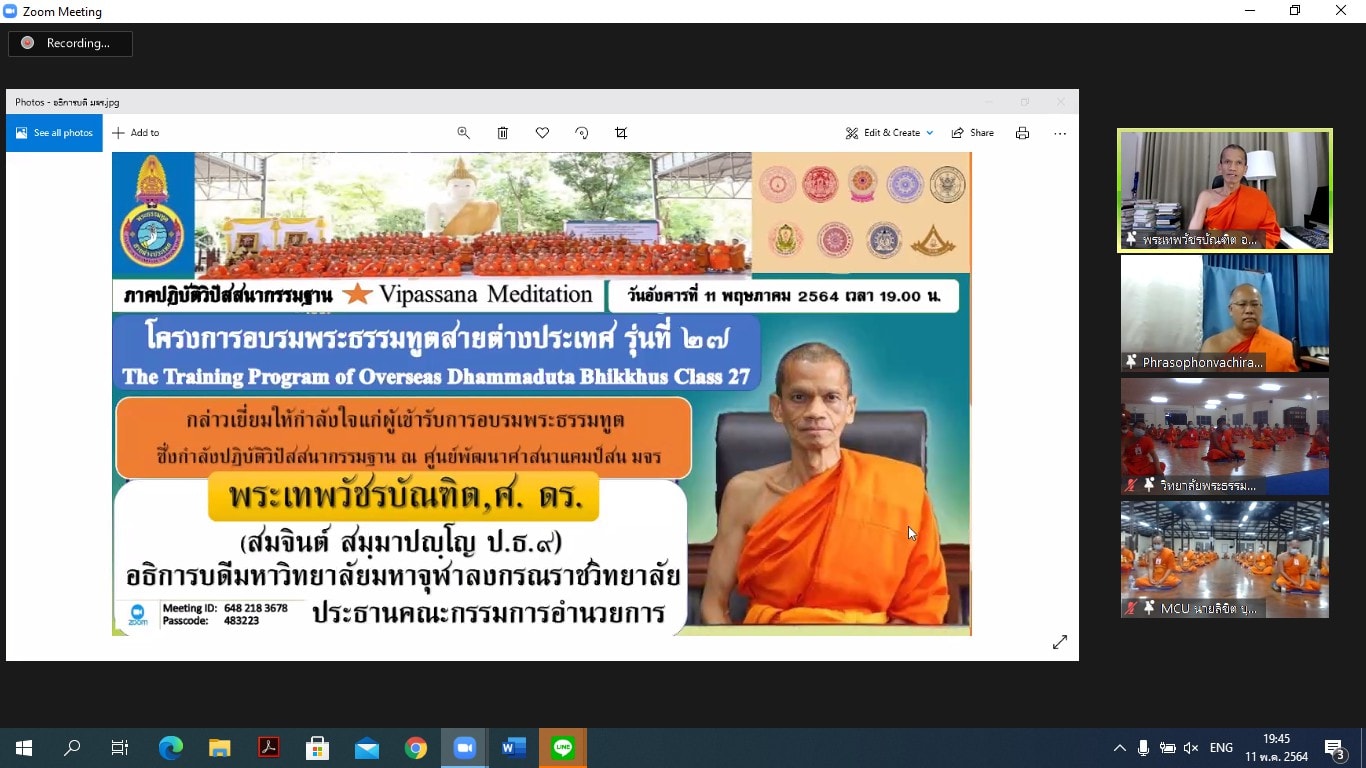

18 April -18 May, 2564/2021 MCU CENTER, PHETCHABUN PROVINCE: The Training program of Overseas Dhammaduta Bhikkhus, Class 27th/2021 has been conducted by Dhammaduta College, Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Thailand. The training program is chaired by Dr. Phra Sophonvachirabhorn, (Sawai Chotiko), Agga Maha Pundita, Vice Rector for Foreign Affairs of MCU, Executive committee, Dhammaduta College, lecturers and administer of International Relations Division of MCU to manage the program.

Overseas Dhammaduta Bhikkhus Class 27/2021 have practiced Vipassana meditation during one month from 17th April to 18th May 2564/2021 instructed by Master Meditations following the method of Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta, The Great Discourse on the Establishing of Awareness

Mindfulness means the ability to keep something in mind. On the Buddhist path, it functions in three ways: remembering to stay alert to what you’re doing in the present moment; remembering to recognize the skillful and unskillful qualities that arise in the mind; and remembering how to effectively abandon the qualities that get in the way of concentration, then developing the skillful ones that promote it.

The Satipatthana Sutta—The Establishing of Mindfulness Discourse—gives detailed instructions in the first two of these functions. It starts with the basic formula for establishing mindfulness, describing four frames of reference for anchoring mindfulness in the present moment. Then it asks and answers questions that focus solely on the beginning part of the formula: how to remain focused on each frame in and of itself.

To give you a sense of how the Buddha would recommend getting started in mindfulness for the sake of true happiness, here is the entire translated discourse.

The practice of the four-fold satipaṭṭhāna, the establishing of awareness, was highly praised by the Buddha in the suttas. Mentioning its importance in the Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta, the Buddha called it ekāyano maggo – the only way for the purification of beings, for overcoming sorrow, for extinguishing suffering, for walking on the path of truth and for realising nibbāna (liberation).1

In this sutta, the Buddha presented a practical method for developing self-knowledge by means of kāyānupassanā (observation of the body), vedanānupassanā (observation of sensations), cittānupassanā (observation of the mind), and dhammānupassanā (observation of the contents of the mind).2

To explore the truth about ourselves, we must examine what we are: body and mind. We must learn to observe these directly within ourselves. Accordingly, we must keep three points in mind: 1) The reality of the body may be imagined by contemplation, but to experience it directly one must work with vedanā (body sensations) arising within it. 2) Similarly, the actual experience of the mind is attained by working with the contents of the mind. Therefore, in the same way as body and sensations cannot be experienced separately, the mind cannot be observed apart from the contents of the mind. 3) Mind and matter are so closely inter-related that the contents of the mind always manifest themselves as sensations in the body. For this reason the Buddha said:

Vedanā-samosaraṇā sabbe dhammā.3

Everything that arises in the mind flows together with sensations.

Therefore, observation of sensations offers a means – indeed the only means – to examine the totality of our being, physical as well as mental.

Broadly speaking, the Buddha refers to five types of vedanā:

-

Sukhā vedanā – pleasant sensations

-

Dukkhā vedanā – unpleasant sensations

-

Somanassa vedanā – pleasant mental feeling

-

Domanassa vedanā – unpleasant mental feeling

-

Adukkhamasukhā vedanā – neither unpleasant nor pleasant sensations.

In all references to vedanā in the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta the Buddha speaks of sukhā vedanā, dukkhā vedanā, i.e., the body sensations; or adukkhamasukhā vedanā, which in this context also clearly denotes neutral body sensations.

The strong emphasis is on body sensations because they work as a direct avenue for the attainment of fruition (nibbāna) by means of “strong dependence condition” (upanissaya-paccayena paccayo), i.e., the nearest dependent condition for our liberation. This fact is succinctly highlighted in the Paṭṭhāna, the seventh text of Abhidhamma Piṭaka under the Pakatūpanissaya, where it is stated:

Kāyikaṃ sukhaṃ kāyikassa sukhassa, kāyikassa dukkhassa, phalasamāpattiyā upanissayapaccayena paccayo.

Kāyikaṃ dukkhaṃ kāyikassa sukhassa, kāyikassa dukkhassa, phalasamāpattiyā upanissayapaccayena paccayo.

Utu kāyikassa sukhassa, kāyikassa dukkhassa, phalasamāpattiyā upanissayapaccayena paccayo.

Bhojanaṃ kāyikassa sukhassa, kāyikassa dukkhassa, phalasamāpattiyā upanissayapaccayena paccayo.

Senāsanaṃ kāyikassa sukhassa, kāyikassa dukkhassa, phalasamāpattiyā upanissayapaccayena paccayo.4

Pleasant body sensation is related to pleasant sensation of the body, unpleasant sensation of the body, and attainment of fruition (nibbāna) by strong dependence condition.

Unpleasant body sensation is related to pleasant sensation of the body, unpleasant sensation of the body, and attainment of fruition by strong dependence condition.

The season (or surrounding environment) is related to pleasant sensation of the body, unpleasant sensation of the body, and attainment of fruition by strong dependence condition.

Food is related to pleasant sensation of the body, unpleasant sensation of the body, and attainment of fruition by strong dependence condition.

Lying down and sitting (i.e., the mattress and cushions, or the position of lying, sitting, etc.) is related to pleasant sensation of the body, unpleasant sensation of the body, and attainment of fruition by strong dependence condition.

From the above statement it is clear how important vedanā, sensation, is on the path of liberation. The pleasant and unpleasant body sensations, the surrounding environment (utu), the food we eat (bhojanaṃ), and the sleeping and sitting position, the mattress or cushions used, etc. (senāsanaṃ) are all responsible for ongoing body sensations of one type or another. When the sensations are experienced properly, as the Buddha explained in Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta, these become the nearest dependent condition for our liberation.

There are four dimensions to our nature: the body and its sensations, and the mind and its contents. These provide four avenues for the establishing of awareness in satipaṭṭhāna. In order that the observation be complete, we must experience every facet, which we can only do by means of vedanā. This exploration of truth will remove the delusions we have about ourselves.

In the same way, to come out of the delusion about the world outside, we must explore how the outside world interacts with our own mind-and-matter phenomenon, our own self. The outside world comes in contact with the individual only at the six sense doors: the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body and mind. Since all these sense doors are contained in the body, every contact of the outside world is at the body level.

The traditional spiritual teachers of India, before the Buddha, in his day and afterwards, expressed the view that craving causes suffering and that to remove suffering one must abstain from the objects of craving. This belief led to various practices of penance and extreme abstinence from external stimuli. In order to develop detachment, the Buddha took a different approach. Having learned to examine the depths of his own mind, he realized that between the external object and the mental reflex of craving is a missing link: vedanā. Whenever we encounter an object through the five physical senses or the mind, a sensation arises; and based on the sensation, taṇhā (craving) arises. If the sensation is pleasant we crave to prolong it, if it is unpleasant we crave to be rid of it. It is in the chain of Dependent Origination (paṭiccasamuppāda) that the Buddha expressed his profound discovery:

Saḷāyatana-paccayā phasso

Phassa-paccayā vedanā

Vedanā-paccayā taṇhā.5

Dependent on the six sense-spheres, contact arises.

Dependent on contact, sensation arises.

Dependent on sensation, craving arises.

The immediate cause for the arising of craving and, consequently, of suffering is not something outside of us but rather the sensations that occur within us.

Therefore, just as the understanding of vedanā is absolutely essential to understand the interaction between mind and matter within ourselves, the same understanding of vedanā is essential to understand the interaction of the outside world with the individual.

If this exploration of truth were to be attempted by contemplation or intellectualization, we could easily ignore the importance of vedanā. However, the crux of the Buddha’s teaching is the necessity of understanding the truth not merely at the intellectual level, but by direct experience. For this reason vedanā is defined as follows:

Yā vedeti ti vedanā, sā vediyati lakkhaṇā, anubhavanarasā…6

That which feels the object is vedanā; its characteristic is to feel, it is the essential taste of experience…

However, merely to feel the sensations within is not enough to remove our delusions. Instead, it is essential to understand the ti-lakkhaṇā (three characteristics) of all phenomena. We must directly experience anicca (impermanence), dukkha (suffering), and anatta (selflessness) within ourselves. Of these three, the Buddha always stressed the importance of anicca because the realization of the other two will easily follow when we experience deeply the characteristic of impermanence. In the Meghiya Sutta of the Udāna he said:

Aniccasaññino hi, Meghiya, anattasaññā saṇṭhāti, anattasaññī asmimānasamugghātaṃ pāpuṇāti diṭṭheva dhamme nibbānaṃ.7

In one, Meghiya, who perceives impermanence, the perception of selflessness is established. One who perceives what is selfless wins the uprooting of the pride of egotism in this very life, and thus realizes nibbāna.

Therefore, in the practice of satipaṭṭhāna, the experience of anicca, arising and passing away, plays a crucial role. This experience of anicca as it manifests in the mind and body is also called vipassanā. The practice of Vipassana is the same as the practice of satipaṭṭhāna.

The Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta begins with the observation of the body. Here several different starting points are explained: observing respiration, giving attention to bodily movements, etc. It is from these points that we can progressively develop vedanānupassanā, cittānupassanā and dhammānupassanā. However, no matter from which point the journey starts, stages come which everyone must pass through on the way to the final goal. These are described in important sentences repeated not only at the end of each section of kāyānupassanā but also at the end of vedanānupassanā, cittānupassanā and each section of dhammānupassanā. They are:

-

Samudaya-dhammānupassī vā viharati.

-

Vaya-dhammānupassī vā viharati.

-

Samudaya-vaya-dhammānupassī vā viharati.8

-

One dwells observing the phenomenon of arising.

-

One dwells observing the phenomenon of passing away.

-

One dwells observing the phenomenon of arising and passing away.

These sentences reveal the essence of the practice of satipaṭṭhāna. Unless these three levels of anicca are experienced, we will not develop paññā (wisdom) – the equanimity based on the experience of impermanence – which leads to detachment and liberation. Therefore, in order to practise any of the four-fold satipaṭṭhānā we have to develop the constant thorough understanding of impermanence which in Pāli is known as sampajañña.

Sampajañña has been often misunderstood. In the colloquial language of the day, it also had the meaning of “knowingly.” For example, the Buddha has spoken of sampajānamusā bhāsitā,9 and sampajāna musāvāda10 which means “consciously, or knowingly, to speak falsely.” This superficial meaning of the term is sufficient in an ordinary context. But whenever the Buddha speaks of vipassanā, of the practice leading to purification, to nibbāna, as here in this sutta, then sampajañña has a specific, technical significance.

To remain sampajāno (the adjective form of sampajañña), one must meditate on the impermanence of phenomena (anicca-bodha), objectively observing mind and matter without reaction. The understanding of samudaya-vaya-dhammā (the nature of arising and passing away) cannot be by contemplation, which is merely a process of thinking, or by imagination or even by believing; it must be performed with paccanubhoti 11 (direct experience), which is yathābhūta-ñāṇa-dassana 12 (experiential knowledge of the reality as it is). Here the observation of vedanā plays its vital role, because with vedanā a meditator very clearly and tangibly experiences samudaya-vaya (arising and passing away). Sampajañña, in fact, is directly perceiving the arising and passing away of vedanā, wherein all four facets of our being are included.

It is for this reason that the three essential qualities – to remain ātāpī (ardent), sampajāno, and satimā (aware) – are invariably repeated for each of the four satipaṭṭhānas. And as the Buddha explained, sampajañña is observing the arising and passing away of vedanā.13 Hence the part played by vedanā in the practice of satipaṭṭhāna should not be ignored or this practice of satipaṭṭhāna will not be complete.

In the words of the Buddha:

Tisso imā, bhikkhave, vedanā. Katamā tisso? Sukhā vedanā, dukkhā vedanā, adukkhamasukhā vedanā.

Imā kho, bhikkhave, tisso vedanā. Imāsaṃ kho, bhikkhave, tissannaṃ vedanānaṃ pariññāya cattāro satipaṭṭhānā bhāvetabbā.14

Meditators, there are three types of body sensations. What are the three? Pleasant sensations, unpleasant sensations and neutral sensations. Practise, meditators, the four-fold satipaṭṭhānā for the complete understanding of these three sensations.

The practice of satipaṭṭhāna, which is the practice of Vipassana, is complete only when one directly experiences impermanence. Sensations provide the nexus where the entire mind and body are tangibly revealed as impermanent phenomena, leading to liberation.

https://tipitaka.org/stp-pali-eng-parallel

Ebook: Beginners Mahasatipatthana-english

News: International Relations Division

Reporter: Phra Siriwanna Siriwanno, IRD

English News: Phra Siriwanna Siriwanno, IRD

Picture: Foreign Affairs of MCU